Harvest Time for a Beloved Palestinian Cauliflower

This month, we feature a story from seed activist and founder of the Palestinian Heirloom Seed Library, Vivien Sansour, about a beloved heirloom cauliflower that comes into bloom only in February. Vivien’s stories of Palestinian heirloom seeds from wheat to watermelon illuminate the importance of Palestinian people, indigenous knowledge, and their contributions to global agriculture. So resilient and drought-tolerant are many of the heirloom seeds that Vivien works to protect, their value has been recognized through history by many people outside the Palestinian culture- including the USDA who gathered seeds from Palestinian farmers between 1913 and the 1940s.

In Palestine’s agricultural traditions, February is a celebratory month when one of the people’s most beloved crops should be blooming and brightening up the streets everywhere. This vegetable beauty is a bright yellow heirloom cauliflower with magnificent green leaves called “zahara baladi,” which means “the heirloom flower” in Arabic.

At the time of our interview a couple of years ago, these heirloom, or “baladi” (literally meaning “of my country” in Arabic) crop varieties- were already under threat due to land loss, political barriers, agribusiness, and other factors. Now, more than ever- not only are the seeds threatened with extinction but the people to whom they belong. It is our vision that sharing such stories can keep alive the seeds of a deeply land-loving culture until they are safe to sprout again.

Hearing the names in their native language elicits the depth of connection that Palestinian people have grown over time between themselves, their plants, and their land. Vivien explained to me that in the Arabic language, particularly in Palestine, parents often refer to their children as their “seeds” or “plants.” Vivien explains that cultural expressions such as these are disappearing as they are seen as a “country” way of talking. “But,” smiles Vivien, “You still hear it- particularly in villages- people will say, ‘Oh, these are your plants, your seeds?” meaning “these are your children?”

The kinship between people and plants in Palestinian culture extends elsewhere as well. For example, Sansour draws the parallel between the gestation period of the heirloom cauliflower and that of a human child. The sense of responsibility and care on the part of the farmer are as real as it would be with a child. “This heirloom cauliflower is a seed that we put in the ground in May. It takes nine months to harvest the cauliflower with zero irrigation. No irrigation. This is a technology of our ancestors in Palestine who worked in this co-creative relationship with nature, just the way we co-create our children.” says Sansour.

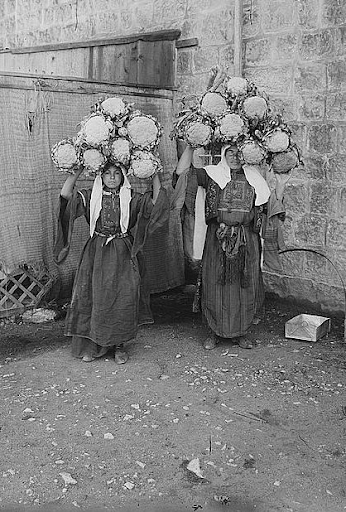

Photos of zahara baladi markets 1890-1940 reposted from the X account of @saalaaaam

As for the taste of the cauliflower: “It’s very sweet. It's delicious. It's also very, very yellow. And we wait for it. February is when we eat it and harvest it. And it's almost like a national pageant. Because people come with their trucks and they stage their cauliflowers in a way to be attractive. And it's so yellow with the green stems, so it pops up on the street wherever you're going. Then there's an old tradition where we have an auction. So the farmers bring their cauliflowers- which is also important in a practical sense because the farmers get to decide the price of their produce. There's no middle person.” Sansour reminisces about the elders who get up on the loudspeaker and call out prices until each head of cauliflower is won by the highest bidder. Sansour tells me she would always buy two heads of cauliflower- one to bring home, and the other to eat in the car on the way home because they were so delicious. The excitement of the auctions are then followed by the enjoyment of making pickles and various cooked dishes such as Makloubeh, a dish of chicken, rice, and cauliflower.

Vivien refers to the heirloom cauliflower from time to time as “she” and “her,” explaining that there is no such thing as “it” in the Arabic language. To Vivien, the cauliflower “is such a precious seed because it grows without consuming and abusing. It doesn’t demand that you dig wells, it doesn’t demand that you put in irrigation lines. The expression we have in Palestine for these heirloom plants is that: “It knows the soil.” So, the story of the heirloom cauliflower encompasses the relationship with land, how we can engage in relationship with the nature that we’re part of, versus in power. I learn a lot from the cauliflower because it teaches me how to be in relationship.”

Photo of Vivien Sansour by @samarhazboun from the Facebook page of Hidden Palestine

To learn more about Sansour’s work, you can visit her website: https://viviensansour.com/